Docker is a software container service which has become quite popular when deploying applications. Basically, it allows you to package software in a way that's conceptually similar to a Virtual Machine. Unlike VM's, containers do not contain platform software, so they are very lightweight and portable. Your packaged software will always run the same in any platform where Docker runs.

The technology introduces some new terms, which may be confusing when you first start using Docker. What's a Docker image? What's a Docker container? How do I run it? This post tries to explain all these terms in the most straightforward way and with a very basic example.

The first step is getting Docker, you can get it for Mac, Windows, and all of the popular GNU/Linux distributions.

Once Docker is installed, you need to create a Dockerfile. A Dockerfile is a set of instructions for Docker to build an image. Think of it as the blueprint or source code. By default, Docker will look for a file named Dockerfile with no extension. You can use the -f argument to specify a different file, but it's a good practice to use this default name and have one Dockerfile per directory if you need to build more than one image in a project.

Let's start writing our Dockerfile:

FROM ruby:alpine

WORKDIR /cultivate

What we're saying here is "I want to base my image on ruby:alpine". This is going to build on top of said image. You can explore Docker Hub and Docker Store which are repositories of Docker images. We are using ruby:alpine, since we are going to run some Ruby code. This provides us a lightweight Linux distribution with Ruby in it. The alpine image is a popular starting point due to it being very small (~5MB) and minimal.

We're also saying "use /cultivate as our working directory`". We'll then add some more things to our Dockerfile for it to do something:

FROM ruby:alpine

WORKDIR /cultivate

EXPOSE 4000

RUN apk add --no-cache bash wget

RUN wget https://media.giphy.com/media/4a7u0GC5hzdgk/giphy.gif -O shark.gif

CMD ruby -run -e httpd . -p 4000

We're asking Docker to expose port 4000, and install bash and wget, because Alpine Linux is that minimal. We then run wget to download a gif file and save it to shark.gif. Last, we use CMD, which provides defaults for an executing container. This is just running a Ruby command which serves the current directory (/cultivate which we defined in WORKDIR') for the web in port 4000.

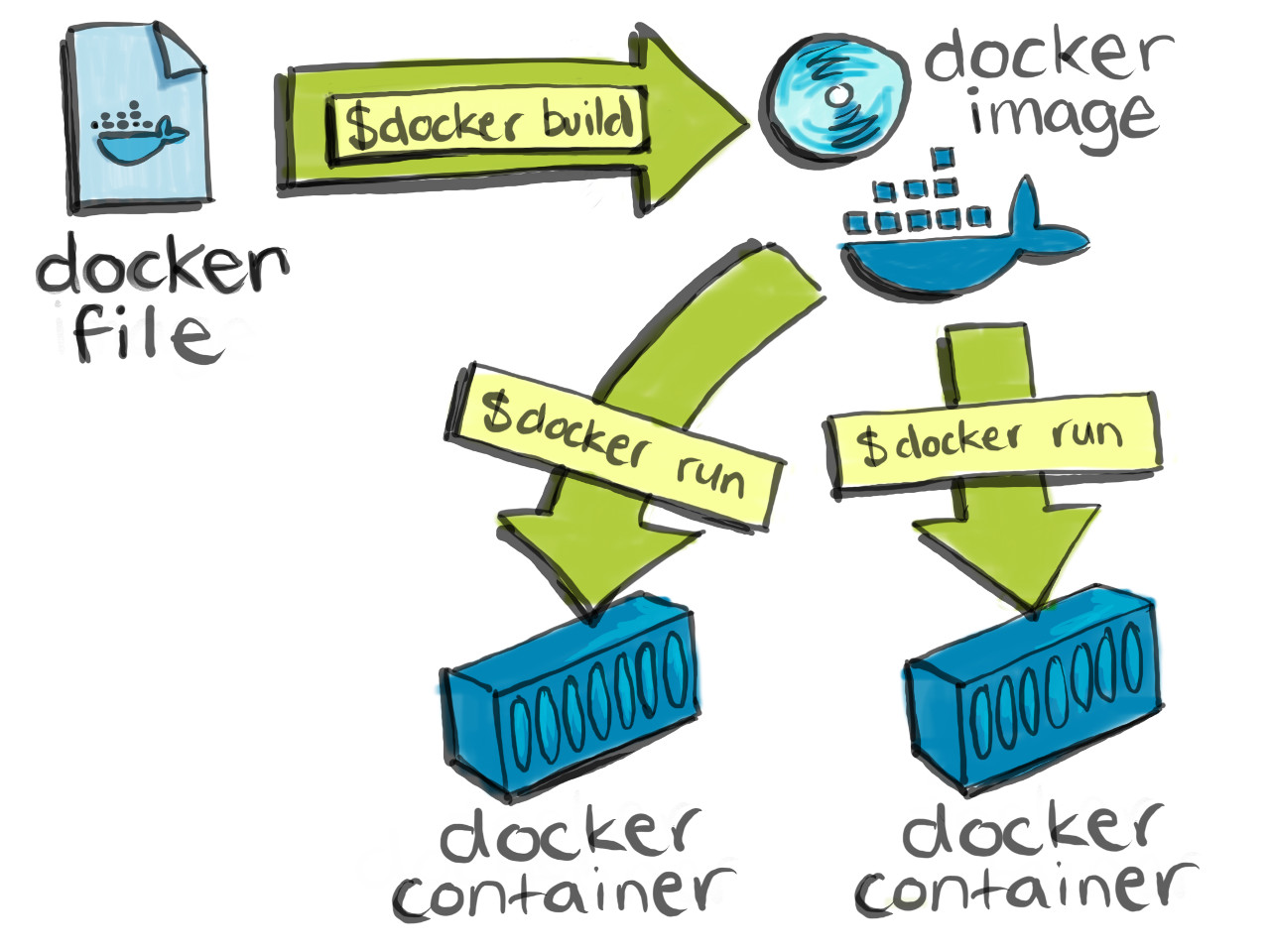

It's probably a good time to talk about Docker images and Docker containers. Once you have your Dockerfile set up, you build a Docker Image with it. Something that's helped me understand what an image is, is comparing it to an ISO image (for when you burn a CD or USB stick). It's not exactly the same, but that's the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about an "image". If you're coming from the Object Oriented Programming paradigm, an image would be a class.

With an image, you can run Docker containers. These would be the "objects", following the OOP paradigm as before. You can run many Docker containers with the same image. You can also build an image on top of other images, like we're doing in this example on top of ruby:alpine.

Since we have our Dockerfile all set up, we can now build it:

$ docker build -t cultivate/shark .

We need to tell docker build where the Dockerfile is, so we're passing . as a parameter to say it's in the current directory. The -t parameter allows us to give a name and optionally a tag (with the name:tag format) to our image, which has now been built:

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

cultivate/shark latest bfdc7a404c0e 3 seconds ago 59MB

So now we can run a container from this image using its ID:

$ docker run -i -t -p 4242:4000 cultivate/shark

For interactive processes (like a shell), we have to use -i -t together in order to allocate a tty for the container process, which is often written -it. We're telling Docker to map our system's port 4242 to the container's port 4000 (with -p).

If we visit http://localhost:4242/shark.gif in our browser, we'll see a very nice image of a shark. You can use any port, like port 80 or port 3000, but beware these ports may be in use (particularly 80 is the default port for web servers). Since these are containers, based on our image, we can run another instance, say on port 9090:

$ docker run -i -t -p 9090:4000 cultivate/shark

The same image of a shark will be available in http://localhost:9090/shark.gif.

Hopefully this diagram will make it even easier to grasp the concept:

You can read more info and learn more about Docker in its official Getting started guide or just visit the Official Documentation.